From Stalled Transformations to Stable Operations: How Floor Presence, Standards, and Teaching Create Real Change

Why manufacturing teams don’t fail for lack of ideas, but for lack of visibility, alignment, and the ability to scale what works.

In this issue of FRAME, we explore what actually drives sustainable improvement. Not slogans. Not dashboards. But presence, clarity, and the often overlooked skill of teaching.

You’ll find lessons drawn from factory floors in Japan, breakdowns of response time versus repair time, examples of how standards like centerlines create operational consistency, and why your ability to teach might be the most underrated skill in your career.

If you care about building stronger systems, developing leadership that matters, and executing change that lasts beyond the kickoff meeting, this issue is for you.

Subscribe at framexl.com to get future editions delivered directly to your inbox.

To learn more about consulting, audits, and technical training, visit joltek.com.

Core Insight: You Can’t Solve Plant Problems from the Boardroom

𝗪𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝗝𝗮𝗽𝗮𝗻 𝗧𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁 𝗠𝗲 𝗔𝗯𝗼𝘂𝘁 𝗩𝗶𝘀𝗶𝗯𝗶𝗹𝗶𝘁𝘆

Years ago, I spent several weeks in Japan during a series of Factory and Vendor Acceptance Tests for Procter & Gamble. I had just passed my first year with the company and, surprisingly, I was the most senior person from our team on site. On the Japanese side, the youngest engineer had already been with the machine builder for five years. When I asked about his experience, he smiled and said he was still learning.

Figure 1 - From Stalled Transformations to Stable Operations | Strategy vs. Presence

That humility was real, but what impressed me more was the depth of training. These were not engineers pushed into roles early. They were deeply immersed in the process. They understood the machinery, the people, the expectations, and the purpose of every detail on the floor. Every engineer I met had spent years walking the line before ever being asked to lead it.

𝗧𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝘄𝗮𝘀 𝗮 𝗱𝗶𝗳𝗳𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝗶𝗻 𝗽𝗮𝗰𝗲, 𝗯𝘂𝘁 𝗮𝗹𝘀𝗼 𝗶𝗻 𝗽𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗰𝗶𝗽𝗹𝗲. Instead of rushing projects to meet a date, they tightened their tolerances. Instead of assuming the customer would find defects during factory acceptance, they checked and double-checked every specification. And most importantly, they brought senior leadership to the floor for every validation. Department heads, plant leaders, and technical specialists stood together as the equipment was tested. They watched. They asked questions. And when problems were found, both sides worked together to solve them immediately. No blame. No delay. Just focused, structured resolution in full view of the people responsible for using the equipment every day.

𝗬𝗼𝘂 𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗲 𝗧𝗼 𝗚𝗼 𝗧𝗼 𝗪𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗣𝗿𝗼𝗯𝗹𝗲𝗺 𝗟𝗶𝘃𝗲𝘀

That moment has stayed with me. Not because it was organized. Because it was honest. I realized something that day that I carry with me still. 𝗬𝗼𝘂 𝗰𝗮𝗻𝗻𝗼𝘁 𝘀𝗼𝗹𝘃𝗲 𝗮 𝗽𝗹𝗮𝗻𝘁 𝗽𝗿𝗼𝗯𝗹𝗲𝗺 𝗯𝘆 𝗿𝗲𝗮𝗱𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗮 𝗿𝗲𝗽𝗼𝗿𝘁. You have to walk the floor. You have to hear the machine. You have to see how operators interact with it, how workarounds form, and how real issues surface in motion.

In North America, we often try to fix operations through strategy meetings and PowerPoint decks. But the reality is that many decisions are made far from the line. And when they are, they miss the nuance. They miss the friction. They miss the impact of a ten-second delay or a misaligned changeover or a half-trained operator trying to keep production going with outdated instructions. 𝗧𝗿𝗮𝗻𝘀𝗳𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗱𝗼𝗲𝘀 𝗻𝗼𝘁 𝗳𝗮𝗶𝗹 𝗯𝗲𝗰𝗮𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗼𝗳 𝗯𝗮𝗱 𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗮𝘀. 𝗜𝘁 𝗳𝗮𝗶𝗹𝘀 𝗯𝗲𝗰𝗮𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗻𝗼 𝗼𝗻𝗲 𝗴𝗼𝗲𝘀 𝘁𝗼 𝗰𝗵𝗲𝗰𝗸 𝗵𝗼𝘄 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗮 𝗳𝗶𝘁𝘀 𝗶𝗻𝘁𝗼 𝗿𝗲𝗮𝗹 𝗽𝗿𝗮𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗰𝗲.

𝗘𝘅𝗲𝗰𝘂𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗟𝗶𝘃𝗲𝘀 𝗢𝗻 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗙𝗹𝗼𝗼𝗿

Most manufacturing teams are not struggling for vision. They are struggling for visibility. A great strategy that ignores operational context will always create more confusion than progress. I have seen beautifully designed rollouts collapse because no one checked whether the people running the machines could actually use the new system. I have seen KPI dashboards that looked great to leadership but meant nothing to the supervisors below them. And I have seen initiatives that completely missed their target simply because no one asked the operator what the real issue was.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗺𝗼𝘀𝘁 𝘀𝘂𝗰𝗰𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗳𝘂𝗹 𝗶𝗺𝗽𝗿𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁𝘀 𝗮𝗿𝗲 𝗮𝗹𝘄𝗮𝘆𝘀 𝗯𝘂𝗶𝗹𝘁 𝗼𝗻 𝗽𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲. Not presence for a tour or a check-in, but presence as a habit. Walking the line. Asking questions. Watching the work as it actually happens. It is not glamorous, but it is where the truth lives.

𝗞𝗲𝘆 𝗧𝗮𝗸𝗲𝗮𝘄𝗮𝘆𝘀

𝗦𝘁𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗴𝗶𝗲𝘀 𝗱𝗼 𝗻𝗼𝘁 𝘄𝗼𝗿𝗸 𝘂𝗻𝘁𝗶𝗹 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝗮𝗿𝗲 𝘁𝗲𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝗮𝗴𝗮𝗶𝗻𝘀𝘁 𝗳𝗿𝗶𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻. If you want a new process to work, you need to take it to the floor and test it with the people doing the job.

𝗣𝗲𝗼𝗽𝗹𝗲 𝗳𝗶𝘅 𝗽𝗿𝗼𝗯𝗹𝗲𝗺𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝗰𝗮𝗻 𝘀𝗲𝗲. The earlier you get leadership involved on the floor, the more context they build. The better they understand how to support real change.

𝗧𝗿𝗮𝗻𝘀𝗳𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗶𝘀 𝗮 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗮𝗰𝘁 𝘀𝗽𝗼𝗿𝘁. You cannot coach it from a distance. You have to be in it. Watching. Learning. Adjusting.

If you want to modernize your operation, begin with the simplest habit you can build. Walk the floor. Do it often. Do it with curiosity. Talk less and observe more. Then ask yourself one question. Is the strategy I am building something that this team can actually use tomorrow? If the answer is no, you have more walking to do.

On the Floor: The Overlooked Discipline Behind High-Performing Lines

Why Centerlines Are Not Just a TPM Tool

Walk into any world-class facility and you will notice something subtle but powerful. Near every major piece of equipment, there is a clear visual or digital reference that tells the operator where the system should be. These are centerlines, and they are not just marks on a machine. They are the foundation of control, consistency, and continuous improvement.

Centerlines capture the ideal operating conditions for key parameters. That could mean roller positions, clamp torque, feed speeds, valve settings, or sensor distances. In essence, they are a contract between engineering, maintenance, and operations. When things go wrong, centerlines provide a known baseline. When things go right, they are the reason performance can be repeated.

The issue is that in many North American plants, centerlines are treated as optional. They are either not documented, not enforced, or quietly bypassed as teams chase daily output. That kind of informal culture is what erodes quality over time.

Figure 2 - From Stalled Transformations to Stable Operations | The Centerline Maturity Curve

Small Deviations Become Big Costs

The most dangerous problems in a plant are not always dramatic. Often, they are slow drifts. A belt tension that is off by just a few newtons. A heat sealer that runs a few degrees too cold. A sensor that creeps a centimeter out of position. Without a centerline, those changes go unnoticed until performance degrades beyond the control of frontline teams.

A study by the Japan Institute of Plant Maintenance found that lack of centerline adherence is one of the top three contributors to chronic minor stoppages. Another benchmarking report from the TPM Awards Council showed that plants with mature centerline systems see an average of 15 to 25 percent improvement in changeover time within the first six months of implementation. That is not a software upgrade. That is not an expensive consultant. That is the result of clarity, visibility, and process ownership.

Lessons from the Floor

In one facility I audited, three identical machines were producing three very different results. When we reviewed the documentation, two of the machines had handwritten settings posted from five years ago. The third had nothing. Operators adjusted settings based on feel. One crew swore the optimal feeder speed was 75 percent. Another insisted it was 68. There was no common truth. Just tribal knowledge and habit.

We brought together line leads, maintenance, and engineering. Over the next week, we ran short controlled batches, captured performance, and documented the best known conditions. Then we locked in the settings and trained every shift. Within three weeks, the scrap rate dropped by nine percent and changeovers stabilized across all crews. No new equipment. No major investment. Just a structured way to hold the process accountable to its potential.

Centerlines Are a Leadership Tool

Here is the real insight. Centerlines are not a technical solution. They are a leadership choice. When they are absent, it tells the team that inconsistency is acceptable. When they are enforced, it signals that standards matter and performance is expected.

The absence of centerlines is not a sign of complexity. It is a sign of neglect. In facilities that invest millions into automation, it is surprising how often no one can answer a basic question: how should this machine be running?

Until that is clear, no digital transformation will fix the chaos. If you want to talk about machine learning, predictive maintenance, or AI on the floor, but you cannot confirm the mechanical position of a forming plate, you are skipping steps.

The Right Time to Start Is Now

You do not need to overhaul the plant. Start with one piece of equipment. Define the settings. Mark them visually. Document them digitally. Train the team. Then measure how performance changes. You might be surprised by how much waste was hiding in those tiny misalignments.

If your operators cannot show you the ideal setup for their station in under sixty seconds, the opportunity is right in front of you. Start with what you can see. Build trust with what you can prove. Lead with what you can repeat. That is the work.

The Metrics That Matter: Why Time to First Action Is the Hidden Cost Driver in Downtime

From the Board to the Wrench

For a period of time, I was the maintenance manager at a Kraft Heinz facility in Fullerton, California. We shut it down in 2018, but the lessons I took from that plant still inform how I look at manufacturing operations today. I led a team of 26 mechanics, technicians, and electricians. Each day, our job was to keep the lines running and keep the team improving. The work was reactive, relentless, and often thankless. But it also provided one of the clearest insights into what truly separates stable operations from constant firefighting.

One metric I tracked obsessively was what I called Time to First Action. It measured how long it took between the moment operations called for support and the moment someone from the maintenance team actually began working on the issue. Not when the line was fixed. Not when the downtime event was logged. But when someone showed up, tools in hand, and started addressing the problem.

What I saw was striking. Sometimes, the team jumped into action in under three minutes. Other times, it took fifteen, twenty, even thirty minutes before anyone moved. And that was not due to laziness or incompetence. It was due to everything else.

Figure 3 - From Stalled Transformations to Stable Operations | Response Time Breakdown

Understanding the Delay Before the Fix

In many plants, metrics like Mean Time to Repair (MTTR) are tracked religiously. But they miss the prelude. The handoffs. The wait time. The confusion. The missing context. The technician searching for the right drawing. The call to a supervisor. The walk across the floor because radios were not working. The operator unsure how to describe what went wrong.

That gap between detection and first response is pure loss. And in reactive plants, it is where the majority of unmeasured waste lives.

A McKinsey report on downtime response patterns found that as much as 30 percent of total downtime is consumed before any repair begins. That is not failure time. That is response time. And it is invisible in most reporting systems.

People, Process, and Clarity

Improving Time to First Action is not just a matter of staffing. It is a function of system clarity. In Fullerton, we began documenting the delay reasons. Sometimes we found process gaps: the notification went to the wrong screen. Sometimes it was resource availability: two techs were already mid-repair. But often, it was a lack of clarity. What was the issue? Who owned it? Did the operator try a reset first?

So we started with what we could control. We trained operators on a basic triage process. We posted visual standards for escalation. We put radio protocols in place to eliminate confusion. We made sure work orders included the right context. Over time, response times improved, not because we hired more people, but because we reduced friction.

Technology Without Clarity is Just Noise

Later in my career, I saw facilities try to automate this response layer with software. They wired up alerts to tablets, screens, and smart watches. But the same delays crept in. Why? Because pushing a notification is not the same as mobilizing action. A sensor alarm that no one understands is just noise. A work order without context is just another task in the queue.

If you want to drive down unplanned losses, you cannot just invest in detection. You need to invest in reaction. That means well-defined escalation protocols, clear task ownership, shared language between ops and maintenance, and most importantly a culture that respects the time between failure and first movement.

Final Thought

You do not need to wait for an expensive integration to start tracking this. Pick a line. Note when an issue is reported. Note when someone begins working on it. Do it for a week. You will quickly see patterns, and you will see where improvement lives.

Because the truth is simple. Until someone starts turning a wrench, no progress is being made. And in the world of manufacturing, minutes are not just numbers. They are margin.

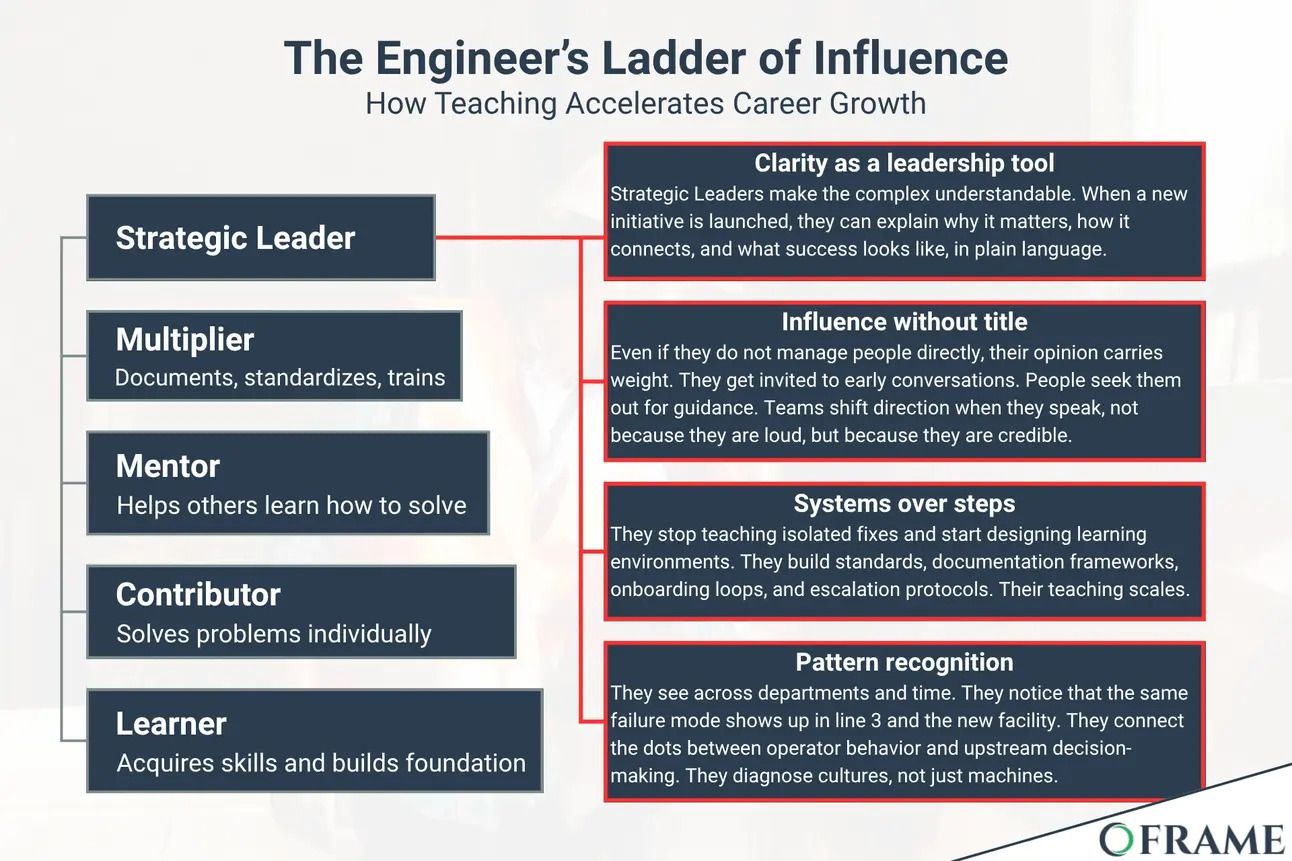

Career Shift: 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗠𝗼𝘀𝘁 𝗨𝗻𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝗖𝗮𝗿𝗲𝗲𝗿 𝗦𝗸𝗶𝗹𝗹 𝗶𝗻 𝗠𝗮𝗻𝘂𝗳𝗮𝗰𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗴 is 𝗞𝗻𝗼𝘄𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗛𝗼𝘄 𝘁𝗼 𝗧𝗲𝗮𝗰𝗵

As many of you know, I consider myself an educator. That may have come from my father who spent most of his life in academia. He had a PhD in nuclear physics, a master’s in computer science, and served as the dean of a university. His career was built on helping others grow. That mindset stayed with me. Even in fast-paced and high-pressure technical environments, I have always found value in being able to explain something clearly, walk someone through a process, or help others succeed by transferring what I know. And over time, I have come to believe something very simple. If you want to grow your career in manufacturing, engineering, or operations, you need to get good at teaching.

Figure 4 - From Stalled Transformations to Stable Operations | The Engineer’s Ladder of Influence

This shows up earlier than most people realize. The first time a junior engineer joins your team, your ability to teach defines whether they contribute quickly or struggle for months. When you roll out a new system, your ability to train others defines whether it sticks. When you troubleshoot downtime on the floor, your ability to walk someone through the logic determines whether they become independent or call you every time it happens again. Teaching is not something extra. It is how knowledge scales. It is how teams stop relying on one person to solve everything. It is how leaders emerge without needing a title.

Most engineers were never taught how to teach. The education system rewards you for solving problems alone. It rarely teaches you to explain your thinking in a way others can use. So when engineers enter the workforce, they often default to the same frustrating cycle. They say things like just watch me or you’ll figure it out or I had to learn the hard way and so should you. That attitude does not build strong teams. It builds dependence. And it erodes performance every time someone leaves, rotates, or burns out.

The best engineers I have worked with shared one thing in common. They did not just understand the system. They could explain it to others in a way that made sense. They slowed down enough to show the why behind their decisions. They adapted how they taught based on the audience. They used visuals, questions, and examples. And they cared whether the person in front of them actually understood. That kind of communication is what builds resilience. It is what keeps a team aligned during high stress. It is what separates a technical expert from a trusted leader.

Teaching also improves your own mastery. If you want to know whether you really understand something, try explaining it to a new operator or junior engineer. You will quickly discover where your assumptions are. You will catch the shortcuts in your logic. You will be forced to clarify what you usually gloss over. That loop of feedback strengthens your own thinking while helping others build theirs. That is a powerful career advantage.

When you are known as someone who can explain the complex in a simple way, your influence grows. You get pulled into earlier conversations. You get trusted with more responsibility. People seek out your opinion. And leadership sees you not just as a technician but as a communicator and decision-maker. The people who can teach well are often the ones who drive change, build trust, and scale progress.

So if you are thinking about your next step, your next role, or your next impact, do not just focus on what you can do. Focus on what you can teach. Invest in the clarity of your explanations. Take time to walk others through your process. Make documentation part of your workflow. And most importantly, pay attention to whether the people around you are getting better because of how you show up. That is what will carry your career farther than any title or tool ever could.

Conclusion

Too many transformation efforts stall not because people don’t care, but because the connection between strategy and execution is broken. You cannot bridge that gap from a meeting room. You have to walk the floor. You have to see what your teams see, understand how they work, and be willing to fix what doesn’t align with reality.

The best manufacturers don’t just rely on tools or titles. They build cultures where presence is normal, standards are visible, and teaching is expected. That is what makes improvement stick. Not just for one project or one person, but across teams, shifts, and years.

If you want to lead meaningful change in your facility, start with what you can control. Show up. Document what works. Teach what you know. And ask better questions every time you walk the line.

Thanks for reading. If this resonated with you, share it with someone who might need to hear it. And if you haven’t already, subscribe at framexl.com and visit joltek.com to see how we help teams take these principles and put them into action.